What movie diner doesn't have a cab driver at the counter, wearing a uniform cap with the company name stiched on the brim while holding forth over a cup of coffee?

Although the buzzword had not yet been minted, the Cab Diner concept had tremendous "synergy" in 1940. In the days before most taxis were radio-dispatched, arranging for a pickup at home was a convoluted process that involved calling a dispatcher, who then called the nearest "cab stand", most often a hotel or restaurant where his company was allowed to station a cab or two for the convenience of the patrons. Calling a diner where a bunch of taxi drivers hung out round the clock was a surer bet than counting on the dispatcher to reach one of his company's cabs at a nearby stand.

Also, taxi drivers were the original deliverers of takeout pizza, egg rolls, and barbeque, not to mention condoms and fifths of gin or scotch. The usual process was that the hungry customer called the restaurant to place his or her order, and the restaurant secured a cab to deliver the meal. A well-stuffed paper bag has never committed robbery and a starving man tends to tip well, especially if the bag of food is being held tantalizingly out of reach as he opens his wallet. However, most drivers considered these runs a crap shoot. The driver had to pay the restaurant out of his own pocket and deliver the food on spec. If there had been any delay, the caller might well have wandered off in search of another meal or the food might be so cold that the would refuse to pay both his bill and the delivery fare. Then the driver might eat a Chinese four course dinner for four for his week's breakfasts, lunches, and dinners. Ordering takeout from a taxicab driver's diner telescopes preparation and delivery and minimizes risk for both caller and driver.

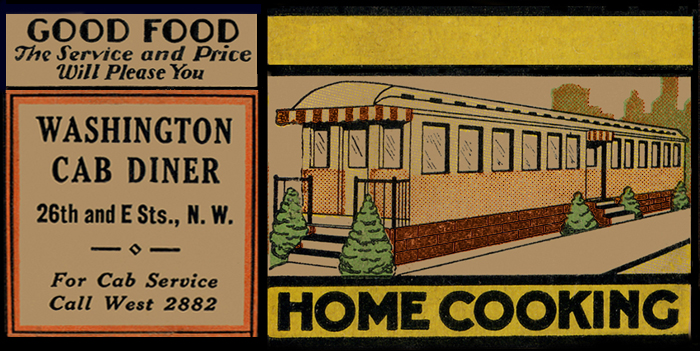

The Cab Diner, which opened in 1938, sat at right angles to the sidewalk along one edge of a gas station plaza at 2610 E Street NW. Although it had a relationship to the Washington Cab Association, whose office was around the corner on 26th Street, it was a family affair under the proprietorship of Carleton Brown and his wife Beulah, who was still running the enterprise in the late 1950s.

Today 's average Washingtonian would have difficulty visualizing the Cab Diner's Foggy Bottom riverfront neighborhood. Peter Penczer's Washington Then And Now photograph shows these blocks around the Heurich Brewery's castle-on-the-Rhine plant as leafy and unpopulated, lacking the familiar curbside ribbons of parked cars even in 1950. But as his text notes, Foggy Bottom was quite industrial, with square blocks devoted to the brewery and the huge storage tanks of the Washington Gas Works. The brewery's eastern battlements faced the original NIH headquarters on the Naval Hospital grounds across 25th Street NW. Even in the 1930s, the briddle path along the Potomac shore attracted several large stables and riding academies, and at least one of the local ice plants followed the Uline Arena example and opened an indoor skating rink. The DC Public Schools football championship was decided annually at Riverside Stadium, which stood on the riverbank near 26th and D Streets into the 1950s.

The Heurich Brewery, the neighborhood's century-old centerpiece and the Cab Diner's landlord, went out of business in 1956 and was demolished for bridge approach construction a few years later. During the early 1960s, this corner of the Foggy Bottom street grid was gradually obliterated to build the expressway loops that, viewed on a landing approach to National, resemble a knot of spider veins. The Cab Diner stayed in business until its block, one of the last survivors, was demolished in 1964.

On a modern street map, it takes a minature T-square to calculate that the Cab Diner would have a prime location today. It stood virtually at the front door of the Kennedy Center. Today

ond,

M

M