|

Dancing in the Moonlight

|

|

|

Elvis Presley's most famous Washington performance was not musical. On the afternoon of December 21, 1970, a beginning- to-bloat Elvis unexpectedly appeared at the White House to offer his services as "Federal Agent At Large". Richard Nixon accepted his gift of a Colt .45 revolver, promised Elvis an honorary DEA badge, and sent him on his way.

But Elvis Presley actually did once play Washington, on a night while Nixon was vice-president and Vietnam was labeled as "French Indochina" on all but the most newest globes.

In 1956 a Washington tradition was meeting a new wave. Beginning in Victorian times, Potomac River steamboat excursions had tempered the summer miseries of the largely non-airconditioned city. Since 1940, the Wilson Line's SS Mount Vernon had cruised to Washington's mansion and the Marshall Hall amusement park each morning and afternoon. By night, a generation of Washingtonians had fallen in love dancing on the Mount Vernon's moonlit decks as the lights of the Potomac shore glided by.

The Mount Vernon herself was part of the romantic setting, with her lithe art deco sillouette, festive "layer cake" color scheme, and gleaming chrome rails. Advertisements stated that she could carry "1,000 dancing couples" on "moonlight cruises" featuring her own band and musical floor shows, as well as contests for such titles as "Miss Connecticut Avenue" or "Most Beautiful Government Employee". Few passengers suspected that beneath her glamorous makeup was a dowager, launched as the Delaware Bay steamer City of Camden in 1916. During 1939 Sun Shipbuilding and the Wilson Line's own Wilmington shipyard had rebuilt the doughty Camden from the hull up to create "the Potomac's first streamliner".

|

|

|

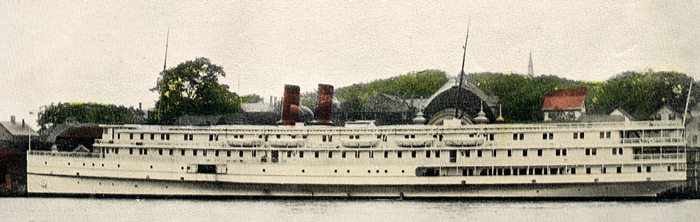

The City of Camden during the World War I years.

|

|

|

The Mount Vernon was a study in pastels during her early years on the Potomac.

|

|

|

By the early 1950s, plans for bridges on profitable ferry routes had made the Wilson Line's corporate future bleak. However, the Potomac excursion trade remained highly profitable, and the Mount Vernon almost outdrew the Washington Senators in some seasons.

The new wave had come with the War. Washington had always been southern in its tastes, but the influx of war workers from Appalachia and the deep south fanned feverish enthusiasm for what was dismissively called "hillbilly music" by the Washington Post. By 1948, an entreprenaur from Lizard Lick, North Carolina with the unlikely name of Connie B. Gay was booking Saturday afternoon "country and western" shows at Constitution Hall. By the mid-1950s, country music had hybridized with rhythym and blues to form "rockabilly". The new music was not sedate enough for most downtown Washington clubs, but it thrived in segregated Anacostia and the bars of "wide-open" Prince Georges County. Some early local heroes like Charlie Daniels, Link Wray, and Roy Clark went on to national fame.

In March,1956, Connie B. Gay booked a young singer who would be passing through Washington between an engagement at the Mosque Theater in Richmond and an appearance on the Dorsey Brothers' televised "Stage Show" in New York. The singer, in spite of being described as a "devastating combination of Frankie Laine, Johnnie Ray, and Billy Daniels" in Dorothy Killgallen's syndicated column, was virtually unknown to adults. However, he had created a modest buzz among teenagers in previous appearances on "Stage Show" and had just released a single called "Heartbreak Hotel" that was simultaneously climbing the "popular", country, and rhythym and blues charts. To showcase the singer, Gay put together a band of local superstars and booked the Mount Vernon for a moonlight dance cruise.

|

|

|

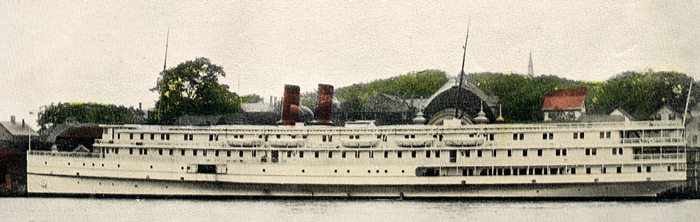

By 1956, the Mount Vernon had adopted a "layercake" color scheme. Traditionalists compared the striped smokestack to a string of Pepsodent toothpaste.

|

|

|

The night of Saturday, March 23, 1956 has become the stuff of local legend. The most commonly-accepted version of events is that Elvis arrived at Pier 4 near Sixth and Water Streets SW to find that his fans had so mobbed the Mount Vernon that she was in danger of sinking. The police had forbidden the ship to sail, but, to forestall a riot, Elvis performed onboard the docked ship and created a sensation that brought his celebrity to critical mass. Washington was denied a second opportunity to witness his triumph because the next day's show was cancelled for "safety reasons".

Parts of the legend check out fifty years later. That evening was one of the few occasions that the Mount Vernon missed a scheduled trip.

At about 6:30 Saturday evening, Elvis was interviewed on the Town and Country Hour, a Connie B. Gay-produced live television show hosted by singer Jimmy Dean. Dean recalled forty years later that Elvis appeared on his show because "there were still tickets left" for the cruise. Dean also recalled that the interview was a personal worst for both Elvis and himself. Without music, Elvis' stage presence deserted him, and he mumbled "yep" and "nope" to questions like "Have you ever performed on a boat?". But a larger crisis was brewing at Pier 4.

While cruising past Fort McNair on the previous afternoon, the Mount Vernon had blown a steam pressure valve. She drifted for a few minutes until the fireboat William A. Belt, summoned by four whistle blasts, towed her to her pier. The Friday evening charter cruise was cancelled, while fitters struggled to restore engine power. Repairs were still incomplete as hundreds of teenagers boarded the boat on Saturday evening, and, just before the scheduled 8:30 PM departure, the announcement was made that the Mount Vernon could not sail. However, Connie B. Gay promised that there would be two shows for the price of one and stood at the gangplank to offer refunds to anyone dissatisfied with his proposition. Reportedly about one hundred people accepted.

The night was cold and blustery, so the remaining crowd abandoned the decks for the glass-enclosed cabin. There was no room to dance, but Elvis played in concert for almost three hours. It is hard to imagine that anyone would leave dissatisfied, but one churlish ticketholder still complained to the Washington Post "in exchange for the $4 I had spent, I had expected to...cruise along the river and dance with my girl."

|

|

|

The original Wilson Line ticket office at the head of Pier 4 is still serving excursion boats.

|

|

|

Because Elvis was due in New York for Sunday rehearsals, the second performance that was cancelled for safety reasons is a myth. Within a week, he was in Hollywood for the screen test which led to a seven year Paramount contract. Within six months, he was savoring a number one album, staring in his first movie, appearing on the Ed Sullivan Show, and buying his mother her first pink Cadillac. The closest he came to a return performance in Washington were concerts at the Capital Center in Largo, Maryland in 1976 and 1977. By then, Elvis was a very different sort of performer.

If March 23, 1956 was simply one point on Elvis' ascending curve of popularity, it was the most notable evening in the Mount Vernon's long career on the river. However, she sailed on into another era, carrying thousands more tourists and revellers, women's clubs and fraternal orders, and couples in search of romance. On January 5, 1964, the crew of a patrolling fireboat noticed that the Mount Vernon, mothballed at her pier for the winter, was listing. Firemen attempted to investigate, but within ten minutes the Mount Vernon had settled on her keel with icy water lapping at her gracefully curved bridge. The cause was later diagnosed as a seacock which cracked from cold weather.

A great outpouring of sentiment and nostalgia followed the sinking of the Mount Vernon. However, her assignment was quickly given to another Wilson Line steamer, the Hudson Belle, rechristened as the George Washington. It was several months before the Wilson Line raised the Mount Vernon, and, although there was talk of refurbishing her, she never returned to excursion service. In 1967, she was sold to the Seafarers International Union, who renamed her the Charles S. Zimmerman after a garment union president. The Seafarers Union built a boxy enclosure on her upper decks and converted her to a floating dormitory at its Harry Lundberg School of Seamanship on Chesapeake Bay. At some point, she left the school and has now presumably been scrapped.

|

|

|

TO RETURN TO THE VICTORIAN SECRETS HOME PAGE, CLICK HERE.

|

|

|

|

|

|